I: The Eastern Christian Interpreters: Solomon Negri, Carolus (Theocharis) Rali Dadichi, John Massabeky, and Phillip Stamma

The first Interpreter of Oriental Languages was appointed by the Crown in 1723.1The post came under the general authority of the Secretaries of the Northern and Southern Departments, which became the Foreign and Home Offices in 1782.2The salary was set at £80.00 a year until 1816.

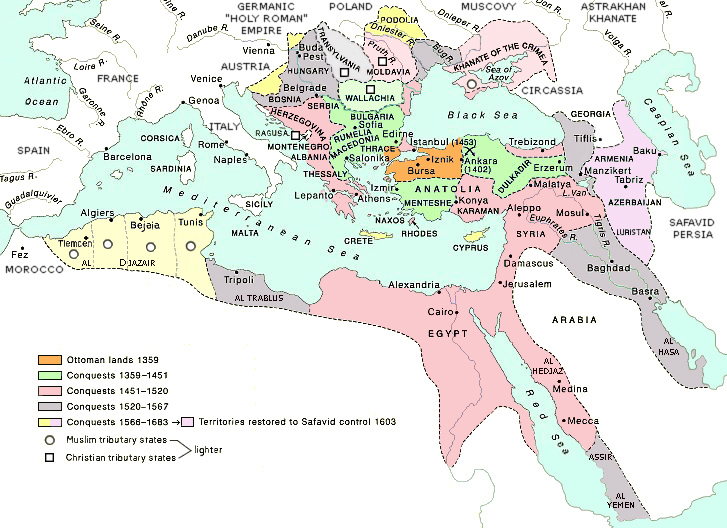

The list of Interpreters of Oriental Languages includes 14 names. They were all bilingual or multilingual men who made a living as translators, interpreters, writers or explorers. There is very little information about three of them, but the other eleven men on our list afford us a glimpse of the varied activities of linguists in Georgian England. Solomon Negri, the first one, was appointed by George I in 1723 and the last one, Abraham Salamé, by George IV, one hundred years later. The position required them to interpret between Arabic and English, often to enable communication between British officials and representatives of the Regencies of Algiers, Tripoli, and Tunis which were nominally part of the Ottoman Empire, as well as those from the Kingdom of Morocco.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

[P]eople who sought to make a livelihood from their skills in Arabic … found themselves in a constant search for students and patrons: for many of them, teaching functioned as but one practice alongside other tasks related to language and writing such as record-keeping, copying, translation, and piecemeal work in libraries and archives.3

The King has ordered that Mr Theocaris Rali Didichi, a native of Aleppo, should succeed Mr Solomon Negri, lately deceased, as his Interpreter of Oriental Languages.4

Apart from his services on behalf of visiting north African diplomats I June 1748 and August 1754, less is known about Stamma’s career than about his reputation as a regular player at the chess club at Slaughter’s Coffee House in St Martin’s Lane.5

Solomon Negri

The first four men on the list were Eastern Christians from Syria, then a part of the Ottoman Empire. Solomon Negri (baptised 1665, d. 1727) was born in Damascus. He was raised in the Eastern Orthodox Church and remained a member of that church throughout a lifetime of exposure to other faiths, through his Jesuit education in Damascus and Paris, his association with (Lutheran) Pietists in Halle, and his work for the (Anglican) Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge in London. He settled in England in 1717 and was buried in the grounds of St Mary-le-Strand on April 5, 1727.6 The Catholic education that the Jesuits gave him in the expectation that he would return to Damascus as a missionary equipped him for working life as a linguist in Europe instead.

Public Domain.

Throughout his career, he took up positions in the fields of diplomacy and Oriental studies and worked for both Catholic and Protestant missionary organisations. He taught Arabic, Syriac, and French. He was employed as an interpreter, translator, editor, and private secretary. He copied, catalogued, and described Oriental manuscripts. He also occasionally acted as an informant to Europeans on matters related to Eastern Christianity and Islam.7

Travels

While there was a market for his skills in Western Europe, Negri was not always satisfied with his lot. His peripatetic life gives some indication of his dissatisfaction with his circumstances: he started off teaching Arabic in Paris, where he also served as a librarian to Jean-François-Paul Lefèvre, the abbé of Paris. He decided against taking up a position at the Bibliothèque Royale because it was not going to pay enough. He moved to London briefly in 1700 – and taught Arabic at St Paul’s School – before moving to Halle to teach for a year. That was followed by stays in Venice and Constantinople, where he studied Turkish and Persian before returning to Italy. He ended up in Rome, where he taught both Syriac and Arabic then took up a position at the Vatican Library.

Many of Negri’s activities are in evidence in his translations, compilations, or letters, not to mention his account of his life, Memoria Negriana (published in 1764 but probably drafted in 1717) but little is known about his interpreting. Two episodes in the Memoria give a sense of how he viewed the role.

Interpreting

In 1705 he heard about plans to open an interpreting school in Venice for interpreters with Turkish and Arabic and applied to direct it. He took himself to Constantinople to improve his command of Turkish in anticipation of taking up the position. He corresponded with the Venetian authorities about books he planned to collect for the school and began gathering pedagogic materials.

The idea, he says, is to ensure that trainees

not just be part of people’s linguistic world but share their mentality, know their history, their politics, and their religion. The approach to take is to immerse young students in the ideas and worldviews of Turkish and Arab people, not just in the nuts and bolts of words and grammar.8

His approach was sensitive to the kind of background knowledge and general culture required of interpreters. His teaching ambitions came to nothing as the school was not set up but his thoughts about the process of interpreting were of some immediate use. He is known to have interpreted for both the Venetian permanent representative and the British ambassador while he was in Constantinople 9

Negri had an interest in diplomacy as well as interpreting. In 1708, he wrote to the French ambassador to Constantinople, applying to the French crown’s envoy to Ethiopia. He had heard about the failed mission – and murder – of the most recent representative sent there and took it upon himself to say how he would do things better. “In his letter, Negri offered a detailed analysis of Du Roule’s missteps, ranging from the ostentation with which he travelled to his having enlisted an uneducated Copt as his interpreter.” He stressed his savoir-faire, education, command of ancient Greek, Latin, French, Italian, Hebrew, Syriac, and Arabic, and his lifetime of travel. When that came to nothing, he wrote to the ambassador again, hoping to be appointed royal interpreter or translator. He stressed his language qualifications, worldliness, his eagerness to return to France and serve the king. He was even prepared to take on the role of professor at the Collège Royal, pointing out that the current chair of Arabic – and royal interpreter – did not have strong enough Latin to ensure accurate renderings from oriental languages He did not get anywhere with those applications either.10

The Memoria, along with Negri’s surviving correspondence, gives us a sense of how a jobbing linguist with good connections survived in eighteenth-century Europe. He undertook one last round of position-seeking when he settled in London in 1717, having decided during a second stay in Halle that the weather there was intolerable. He had visited London before and met Anton Wilhelm Böhme, the German chaplain of St James’s, who was a crucial mediator between the Pietists in Halle and the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SPCK) in London. Negri became involved in a SPCK project: he wrote to the Society in March 1720 in favour of the publication of the New Testament in Arabic.

He then proposed a well-translated, well-formatted, well-printed New Testament and Psalter that he assured would be welcomed enthusiastically by the sizable Christian communities of the Middle East.11

Public Domain.

(Hill’s portrait of Negri has disappeared.)

Negri also translated two Arabic medical texts into Latin, as well as acting librarian for Humfrey Wanley, an antiquary for whom he identified oriental manuscripts. His time in London seems to have been fairly settled and successful. “It was this period that marked Negri’s growing ties to a circle of individuals that would, over and over again, facilitate Negri’s attainment of specific posts.”12 Wanley was librarian to the first and second earls of Oxford; through him, Negri joined their circle of antiquaries and had his portrait painted by Wanley’s friend, Thomas Hill. He became well-established in the world of oriental linguists in London, which may be how he came to be appointed the King’s Interpreter of Oriental Languages.

Carolus (Theocharis) Rali Dadichi

The next Interpreter of Oriental Languages on our list, Carolus Rali Dadichi (ca. 1693-1734) had much in common with Solomon Negri. He too was a well-connected Eastern Christian who was educated in Paris. He was one of two children selected in 1707 by the French Naval Minister to attend the Jesuit college, Louis Le Grand, where he studied the humanities and philosophy, and learned Greek, Latin, Italian, and Spanish as well as French. The expectation was that he would return to his native Aleppo as a pro-French Catholic missionary. Like Negri, he stayed in Europe instead; his ship home had to shelter in Livorno during a storm and he decided to stay on the Continent.

Wikipedia.

Travels

After stays in Venice and Rome, Dadichi headed North to Geneva and Zurich before moving to Strasbourg, in 1717. He boarded with the philologist Johann Heidrich Lederlin and taught him Arabic. Much of what we know about his life comes from a 1718 letter applying for funding from the University of Marburg. He later went to Halle where he taught Syriac and Arabic at the Collegium Orientale Theologicum. In 1720, he moved to Berlin. During his travels, “he secured a succession of private and institutional patrons, teaching Arabic, cataloguing collections of manuscripts, and assisting in a number of translation projects, leaving in his wake a paper trail of his European contemporaries’ testimonies to his prodigious skills as a linguist.”13

England

Dadichi moved to England in 1723, where he was known as Theocharis Rali Dadichi. Here too there are parallels with Negri’s life. He was introduced to the SPCK and did some translation and editorial work for them on the New Testament and the Psalter, as well as transcribing manuscripts sent to the Society from Aleppo.

A part of his income during his first years in the country was scraped together from payments received from the SPCK for transcribing the manuscripts from Aleppo, translating Sherman’s notes to the New Testament from Arabic into Latin, preparing fair copies of the Psalter and the New Testament for the printer, and correcting the sheets as they came from the press. The happy news of Dadichi’s recruitment to the project was communicated to Sherman … ‘Good Providence has sent to England Mr Dadichi an Ingenious Learned Native of Aleppo to assist in the correcting part’; this … is a circumstance I am very glad to acquaint you with, Mr Negri being much in years’.14

Dadichi did not leave as much correspondence as Negri, so it is harder to get a sense of what he made of his wanderings. There are some indications that he found life a little easier than his predecessor. There is a reference to him in a footnote in Travels of the Jesuits referring to his translation of a piece about a petrified town by the ambassador of Tripoli to the Court of St James, Cassem Aga:

This was Mr Dadichi, born in Aleppo, and educated at Paris; a gentleman famous for his uncommon skill in the Eastern Languages; and in those of Greece and Rome; in the several polite modern ones, and in every Part of Literature; all of which were set off by a very communicative Disposition, of which I was so happy as to receive many Testimonies.15

Dadichi had made a place for himself in England, and his communicative disposition was probably of assistance to him when, in 1727, he was appointed to replace (the late) Negri as Interpreter of Oriental Languages. He held the position until he died, in 1734. Given his range of language-related activities, his appointment was not his only source of income. The title was probably a distinguished – and useful accolade for a freelancer to have.

John Massabeky

Appointment

However little information we may have about Negri’s or Dadichi’s interpreting activities, at least they have left something in the archive. Dadichi’s successor, John Massabeky, has disappeared almost without a trace. His name appears in the records as Interpreter of Oriental Languages from 1734 to 1739. There is a record of a payment made to him on 26 June 1734:

John Massabeky – 80 per annum – As royal interpreter of the Oriental languages, loco Theocaris Rali Didichi (sic), deceased.16

Extra Payment

There is another reference to him on August 17, 1736:

John Massabeky is to be paid 60l. by the hands of Mr. Lowther as royal bounty. 17

This appears to be a payment made in addition to the £80.00 Massabeky is recorded as having received. It could be that the £80.00 annual fee was a retainer of sorts, with extra payments to be made when actual interpreting was required. The records also show that he left office by July 1739.18

Phillip Stamma

Chess

Massabeky’s successor was a minor celebrity. Much of what we know about Phillip (also Philippe, Philippo, or Filipo) Stamma (d. 1755) comes from the preface to his Essai sur le jeu des échecs, which was published in France in 1737. He was born in Aleppo to a wealthy merchant family and travelled to Spain, Italy, and France before moving to England. It was in Paris that he established himself as a chess player, often at the Café de la Régence, frequented by chess luminaries as well as public figures like Denis Diderot or Benjamin Franklin.

In this clubby and intellectual milieu Stamma attracted attention and said time and again that they played chess better in the East than in the West. This became part of the myth around this traveller from Syria who came to be considered the source of modern chess notation.19

Connections

It is thanks to Stamma’s status in the world of chess that we know something about him as a linguist. There were two articles about him in the British Chess Magazine (republished in EG XI) that considered his life story and his connections to members of the French and British ruling classes. Stamma may well have been in the right place at the right time in Paris in the 1730s when his contacts in the world of chess made him known to the Secrétaire d’Etat, Louis Chauvelin, who needed diplomatic and linguistic assistance in his dealings with the North African regencies and Morocco.20 He also became acquainted with William Stanhope, Lord Harrington, the British diplomat, and – from 1730 – Secretary of State for the Northern Department (later the Foreign Office), to whom he dedicated the Essai.

Chauvelin’s fall from grace at court in 1737 – the very year of publication of the Essai – made life very difficult for Stamma. This is where the dedication to Harrington takes on significance, as it includes a reference to the difficult circumstances in which Stamma found himself. He needed help: he was appealing to Harrington as he had lost his patron at the French royal court. The Englishman was moved to assist his chess-playing acquaintance (who was also an occasional informant). Stamma was able to move to London with his wife and son, and in July 1739 he was appointed Interpreter of Oriental Languages.

Wikipedia.

There is much that is cheerfully speculative in this account, which draws on alluring links between chess, diplomacy, informing, and interpreting. It is convincing, however, and the dates fit. Furthermore, unlike other appointments to the post of Interpreter of Oriental Languages, Stamma’s was not occasioned by the death of his predecessor: Massabeky left office on the day Stamma accepted the position, so strings may have been pulled to get him the job. Lord Harrington was, after all, the Secretary of State.

Stamma’s years in office – he served until 1755 – marked the end of an era. He was the last Interpreter of Oriental Languages born in the Middle East. His successor was an Englishman, Richard Stonehewer.

Postscript: Money

While we know that Interpreters of Oriental Languages were paid £80.00 a year, it is hard to get much sense of what that represented. The Secretariat’s Necessary Women (cleaners) earned £14.00 a year. The Translators of German or Southern Languages (Spanish and Italian) received £200.00 a year. The Secretary of State’s allowances added up to £5680.00.21

In the first half of the 18th century, a nurse earned £5.00 to £8.00 a year, a milliner, between 8 and 10 shillings a week, and a seamstress 5 to 6 shillings a week.22 Naval officers began with £15 to £28 per annum as servants or midshipmen; as lieutenants, they made from £73 to £91; and as captains, £10.23

We can also look at what that sum would be worth today. Phillip Stamma was given two extra payments by the Treasury: £224.00 in 1748 and £168.00 in 1754, for interpreting for the ambassadors of Tunis and Morocco. They would be worth £20 000.00 and £15 000.00 today.

I would like to thank Zoë Hewetson and Frances Steinig Huang for their help with the translations.

- https://www.british-history.ac.uk/office-holders/vol2/pp22-58#h2-s47

- https://www.british-history.ac.uk/office-holders/vol2/pp1-21#h3-s2

- Ghobrial, J- P, The Life and Hard Times of Solomon Negri: An Arabic Teacher in Early Modern Europe, pp 310-331, in Loop, J, Hamilton, A. and Burnett, C. eds, 2017. The Teaching and Learning of Arabic in Early Modern Europe. p 31.

- https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-treasury-papers/vol6

- Ghobrial, J-P, 2015 Dictionary of National Biography (DNB) entry on Stamma, Phillip.https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/106962.

- Weston, D, 2013 DNB entry https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/105274

- Manstetten, P Solomon Negri: The Self-Fashioning of an Arab Christian in Early Modern Europe, pp 240–282, in Zwierlein, C ed, 2022, The Power of the Dispersed: Early Modern Global Travelers beyond Integration, p 242.

- My translation. Entreranno cioe non solo nell’universo linguistico, ma nella mentalita di un popolo; ne conosceranno la storia, la politica, la religione. Si tratta, insomma, di immettere i giovani nel circuito delle idee, nella Weltanschauung del popolo turco e arabo, non solo nella meccanica delle parole e della grammatica. Lucchetta, F. Un Progetto per una Scuola di Lingue Orientali a Venezia nel Settecento, in Quaderni di Studi Arabi , 1983, Vol. 1 (1983), pp1-28, p 9.

- Manstetten, Op Cit p 266

- Ibid pp 266-7.

- Lake, A, 2015. The First Protestants in the Arab World: The contribution to Christian mission of the English Aleppo chaplains 1597 – 1782, p 133.

- Ghobrial, Op Cit, p. 319.

- Mills, S 2020. A Commerce of Knowledge: Trade, Religion, and Scholarship between England and the Ottoman Empire, 1600-1760, p 233.

- Mills, S Op Cit p 234. Rowland Sherman was an Aleppo-based merchant with a strong interest in Arabic.

- Lockman, 1743. Travels of the Jesuits, into various parts of the world: compiled from their letters. Now first attempted in English. Intermix’d with an account of the manners, government, religion, &c. of the several nations visited by those fathers: with extracts from other travellers, and miscellaneous notes, p. 251

- British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-treasury-books-papers/vol2/pp 643-655

- https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-treasury-books-papers/vol3Treasury Minute Book XXVII.

- https://www.british-history.ac.uk/office-holders/vol2/pp 85-119

- My translation. C’est dans cette ambiance feutrée et intellectuellement forte que Stamma va attirer les regards et répète à l’envi que l’on joue mieux aux échecs en Orient qu’en Occident. Cette affirmation participera à construire le mythe de ce voyageur débarqué de Syrie, considéré par la suite comme le précurseur de la notation échiquéenne moderne. Hayek, C in L’Orient-Le Jour, 25 August 2021 https://www.lorientlejour.com/article/1272686/philippe-stamma-des-faubourgs-dalep-au-slaughters-house-de-londres.html

- Roycroft, J in EG XI Volume V, pp 215-226, p 221.

- https://www.british-history.ac.uk/office-holders/vol2

- Figures from Peter de Bolla.

- Godwin James, F Clerical Incomes in Eighteenth Century England, Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church, SEPTEMBER, 1949, Vol 18, No. 3, pp. 311-325, p 318

What adventurous lives! Thank you, Christine.