Li Zibiao, George Thomas Staunton and the Macartney Embassy

In 1787, The British government decided to send an embassy to the Chinese imperial court to negotiate more favourable trading conditions than those afforded by the Canton system. Their goals included access to ports other than Canton (Guangzhou), an embassy in Beijing, and an island reserved for British traders’ use. While the first mission failed as the ambassador appointed to lead it died en route, the idea was revived in 1791, and on 6 September 1792, George, Viscount Macartney, and his retinue set sail from Portsmouth in three vessels. The embassy was financed by the East India Company (EIC), which was eager to trade more freely and learn more about life in China so as to know what they might be able to sell there.

Macartney’s embassy was deemed to have failed because the Qianlong Emperor (r 1735-1796) refused to grant Macartney any of the formal requests outlined in a letter. A number of reasons have been put forward for this imperial dismissal. The broad explanations for the failure of the embassy include the clash of civilisations or the different approaches to diplomacy between a rising European power used to diplomatic negotiation involving sovereign states and an ancient empire at the centre of a tribute system that treated other nations as vassal states. Narrower considerations blame Macartney’s supposed reluctance to kowtow to the emperor – or kneel and bow his head to the floor nine times – or the embassy’s poor preparation.

What is unusual about this embassy – the first of two sent from Britain to China – is the wealth of material in both Chinese and English about the ambassador, his retinue, their travels, and their interpreters. This allows for a more detailed consideration of what both sides might have wanted and how those positions were expressed, as shown in Henrietta Harrison’s recent publication, The Perils of Interpreting: The Extraordinary Lives of Two Translators Between Qing China and the British Empire, a dual biography of two interpreters with the embassy, Li Zibiao and George Thomas Staunton.

On the conduct of Lee, our Chinese interpreter, any praise that I could bestow would be far inadequate to his merit. Fully sensible of his perilous situation, he never at any one time shrunk from his duty. At Macao he took an affectionate leave of his English friends, with whom, though placed in one of the remotest provinces of the empire, he still contrives to correspond. The Embassador, Lord Macartney, has had several letters from him; the last of which is of so late a date as March 1802; so that his sensibility has not been diminished either by time or distance.2

With more modest aims, and, perhaps more importantly, a willingness to perform the kowtow, [the Macartney embassy] might have achieved more.3

His [Sir John Barrow’s] participation in the Embassy demonstrates the care with which Lord Macartney chose his companions. Macartney and Staunton knew each other from service in the West Indies and Barrow, a poor boy from the Lake District, had been tutor to young Staunton, Macartney’s page.4

Li Zibiao

On the face of it, Li Zibiao – or Li Jacobus, to use his Christian name – was an unlikely interpreter for the 1792-4 British embassy to China. He was the youngest of a group of eight Chinese Catholics to travel to Naples in 1771 to study for the priesthood at the College of the Holy Family of Jesus Christ – otherwise known as the Naples Chinese College. When he was recruited to travel back to China with the embassy led by Lord Macartney in 1792, he was trilingual in Mandarin, Latin and Italian, but had no English and did not master either formal Chinese or Chinese calligraphy.

Li was selected by George Leonard Staunton, Macartney’s deputy. Both Macartney and Staunton had strong views about what they wanted in an interpreter, having been disappointed by their experience of negotiating the 1784 Treaty of Mangalore. They wanted to be in control, to lead discussions and to feel that their intermediaries were on their side. They did not want to depend on interpreters for the Canton trading system, or Jesuit missionaries at court, as they feared they would not support British ambitions for enhanced trade with China. As Macartney put it, someone recruited in Europe

… might contract in the necessary intimacy of a long voyage, whilst onboard the ship, an attachment which would ensure fidelity and zeal in the service. His sentiments at least and real character could not fail of being discovered, and of shewing what degree of dependence should be placed on him; in all events, he would serve as a check upon the resident missionaries.5

That is how Staunton found himself in Naples in search of reliable linguists with Mandarin – the Northern dialect spoken at the Emperor’s court in Beijing.6 Li was one of two chosen from the Chinese College. The other was Ke Zongxiao, from a Beijing family. The party then travelled to Rome to get authorisation from the Vatican for the two priests to join the embassy. This was necessary because there was a risk that the Chinese authorities would not look kindly on two young men who had travelled overseas without authorisation; if they were sanctioned upon return home, the Vatican’s mission could be jeopardised. Li and Ke were granted an audience with the Pope, who approved their association with the embassy. Staunton was authorised to take two more men home to China: Wang Ying and Yan Kuenren, who had also studied at the College in Naples.

Languages

When initially describing his plans to the religious authorities, Staunton had spoken about the service these linguists could render on the year-long journey to China, underplaying any involvement with the embassy when it was in China. The interpreters were to sail with the ambassador and his retinue; they would be able to communicate with Macartney in Italian – which he had learned on the Grand Tour, speak Latin with the others and help the travellers prepare for their meetings with the Chinese imperial authorities. Staunton had further plans for them: he wanted his eleven-year-old son, George Thomas Staunton to learn Chinese.

Staunton had taken charge of his son’s education after his return from India in 1784. There was a strong language input: he began speaking Latin to him from around the time he was five and later hired the German John Christian Hüttner to tutor him in ancient Greek and Latin, and John Barrow to cover mathematics. When the embassy to China came up, the boy was included. He started learning Chinese with Ke before they set sail, His time on the HMS Lion was to be put to good use: he had three hours a day of Chinese lessons with Ke and one of Greek with Barrow. Those Chinese lessons proved to be Ke’s major contribution to the embassy. He, along with Wang and Yan, decided to leave the embassy when the expedition reached Macao as he feared reprisals from the authorities. That may have been for the best as the “intimacy of a long voyage” had shown him to be ill-humoured and inflexible.7

George Thomas Staunton learned enough Chinese on the voyage to be enlisted in occasional work for the embassy. Macartney thus came to depend on a child and a priest with no English and little high-register Chinese. The nature of the embassy was such that personality and reliability were as important as language skills. Like many early interpreters, these two were in the right place at the right time and contributed open minds and an ability to listen, in the course of a protracted and ultimately unsuccessful attempt to enhance British trade with China.

Mr Plum

It is, of course, impossible to know if Li was acting out of a sense of duty or a spirit of adventure when he agreed to stay on when the embassy sailed from Macao to Tianjin. His background – a Catholic from the north-western frontier region of China with Chinese, Mongol, and Tibetan influences – may also have contributed to his willingness to work with the embassy.8 In his account of this decision George Leonard Staunton further notes that “[h]e was a native of a part of Tartary annexed to China and had not those features which denote a perfect Chinese origin …” 9 In any case, the priest who had earlier agreed to swap the habits he wore at his Naples college for a dark coat and breeches 10 donned an English military uniform, complete with a cockade and a sword. He also decided that he should be known as “Mr Plum,” since that was the English translation of his name.

Interpreters in China

Macartney’s and Staunton’s respect for Li was echoed by the Chinese authorities, for whom diplomatic interpreters were official members of their delegations. There was a Chinese Interpreters and Translators Institute but it concentrated on Arabic, Tibetan, Thai, and Burmese 11 The Qianlong Emperor himself could speak Mongol, Tibetan, and Uyghur and recognised the significance of the role played by interpreters. While other arrangements had been made for Macartney’s audience with him, it was finally decided that Li would interpret at the meeting. Staunton suggests that the Chinese preferred him because – unlike the Jesuits – he did not have a foreign accent. 12

Given the year-long journey, and the time spent in China either travelling or negotiating the terms of the meeting between Macartney and the Qianlong Emperor, which finally took place at his summer palace in Jehol (Chengde) on September 14, 1793, having two intermediaries who were biddable and patient was useful. Li Zibiao was by all accounts outgoing and helpful and did what he could to ease relations between the embassy and the Chinese authorities. He was also prepared to engage in complicated linguistic exercises. George Leonard Staunton gives an example of the kind of work Li and others had to do when he describes what occurred when there was a need for a Chinese translation. Macartney had written a letter outlining his position on the kowtow, but his translator – the secretary to a Jesuit missionary – did not want his handwriting to appear in the official version because he was not authorised to work with these outsiders.

The difficulty was however overcome by means of the youth formerly mentioned as page [George Thomas Staunton] to the Embassador, and who had acquired an uncommon facility in copying the Chinese character, beside having made progress enough in the language to serve sometimes as interpreter. The process for this purpose was somewhat tedious. The English paper was first translated into Latin by Mr. Hüttner, for the use of the Embassador’s Chinese interpreter [Li Zibiao] who did not understand the original. The interpreter explained, verbally, the meaning of the Latin into the familiar language of Chinese conversation, which the new translator transferred into the proper style of official papers. The page immediately copied this translation, fair; when the original rough draught was, for the satisfaction of the translator, destroyed in this presence.13

Giuseppe Castilgione – Palace Museum, Beijing. Public Domain.

The kowtow

The letter proposed a compromise: Macartney would kowtow if a Qing official kowtowed to a portrait of George III in private. As for the kowtow, we will never know what Macartney did when he was ushered into the Qianlong Emperor’s yurt. The Stauntons and Li were the only members of his party present perhaps to ensure that little if anything about the occasion would be revealed. One of the highlights of the audience was George Thomas Staunton’s presentation to the Emperor as the Chinese-speaking member of the party, He was rewarded for this brief exchange with an embroidered purse and a footnote in history.

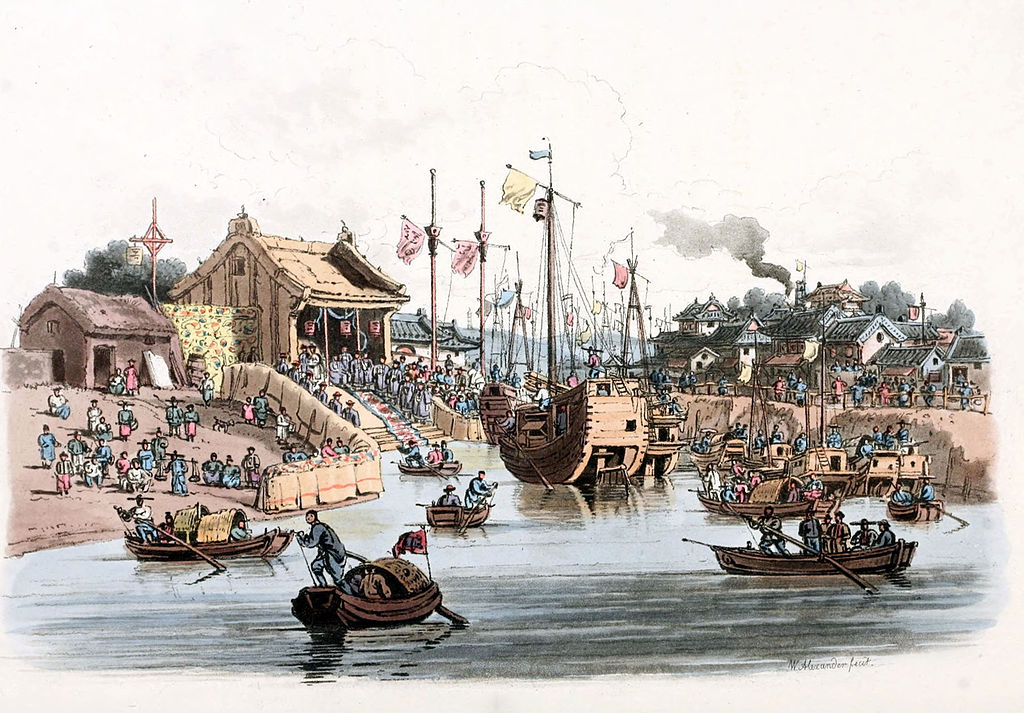

The audience and its attendant meetings with officials had little effect. The embassy was then sent back to Beijing, the Emperor followed and saw the carefully prepared gifts on September 30th. The gifts and embassy did not impress and so they were ordered home on the following day.14The embassy may have failed diplomatically but Macartney and his retinue had spent some six months in China.15 The accounts and illustrations that were published made a lasting impression on the British public and future diplomats.

Throughout his account of the embassy which was based on Macartney’s papers – George Leonard Staunton shows awareness of the working methods used by his translators and interpreters as well as the problems they faced. He sensed that when there was a real engagement in discussions, the “stiffness which generally accompanies a communication through the medium of an interpreter was removed …”.16 He also knew how nerve-wracking it could be. One potential interpreter was so intimidated by the Mandarins paying a visit to Macartney that he was incapable of rendering the ambassador’s message in anything but “the most abject address that the Chinese idiom admitted from persons of the lowest degree.”17

Staunton’s sensitivity was perhaps a reflection of his investment in the embassy. It may also have been informed by his own background: he grew up Protestant in a Gaelic-speaking district of Galway before being sent to a Jesuit College in France. He had learned from early on how to deal with multilingual encounters. Staunton had his standards and was quick to point out perceived difficulties, so his tribute to Li Zibiao, towards the end of his account of the embassy is noteworthy.

As soon as all the ships were ready and assembled near Macao, the Embassador embarked upon the Lion, leaving none of the gentlemen behind who had accompanied him to China, except Mr Henry Baring, now a supercargo at Canton and the Chinese interpreter who, in the dress and name of an Englishman, continued with his Excellency until the moment of his embarkation. This worthy and pious man, after bidding an affectionate farewell to the companions of his travels, and not a little affected by the separation from him, immediately retired to a convent, where he resumed his Chinese dress …18

After 1794

Li Zibiao returned to his vocation after the embassy left China. He was based in the north-eastern Lu’an (Changzhi) for the rest of his life, tending to the Catholic communities scattered across his province. He stayed in touch with friends in Naples and Great Britain over the years. George Leonard Staunton sailed home with his father. The embassy had a determining influence on his life. The boy who had addressed the Qianlong Emperor went on to live and work in China. He joined the EIC in Canton in 1798 and improved his command of Chinese so much that he was able to translate the Chinese legal code into English. He served with the second embassy to China led by Lord Amherst, which has its share of interpreter stories.

- Alexander, W. 1814. Picturesque representations of the dress and manners of the Chinese. Illustrated in fifty coloured engravings, with descriptions. John Murray. London. 1814. Plate 42.

- Barrow, Sir J. Travels in China, 1804. T. Caddell and W. Davies, London. p. 604.

- Andrade, T. 2021. The Last Embassy: The Dutch Mission of 1795 and the Forgotten History of Western Encounters with China. p. 42.

- Dr Wood, F. Britain’s First View of China: The Macartney Embassy 1792-1794. In the RSA Journal, March 1994, Vol. 142, No 5447, pp. 59-68, p. 62.

- Quoted in Harrison, H. 2022. The Perils of Interpreting: The Extraordinary Lives of Two Translators Between Qing China and the British Empire. Princeton U.P. p. 61

- Staunton, Sir G. 1799. An Authentic Account of an Embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China. John Bioren. Philadelphia. Vol. 1 pp. 21-2.

- Harrison. op. cit., p. 87

- Harrison. op. cit. p.17

- Staunton. op. cit. Vol. 1 p. 192

- Harrison. op. cit. p. 66

- Ibid. p. 105

- Staunton. op. cit. Vol. 2 p. 30

- Staunton. op. cit. Vol. 2 p. 32

- https://www.chinasage.info/index.htm

- https://www.chinasage.info/maps/Macartney-embassy-map.jpg is a useful map of the routes taken.

- Staunton. op. cit. Vol 1 p. 241

- Ibid. p. 263

- Staunton. op. cit. Vol. 2 p. 257