In 1584, Elizabeth I granted Walter Raleigh the right to explore and settle any land on the North American continent that was held by non-Christians. Raleigh’s attempts at settlement came to grief but their story reveals something about the role played by interpreters in early English colonialism.

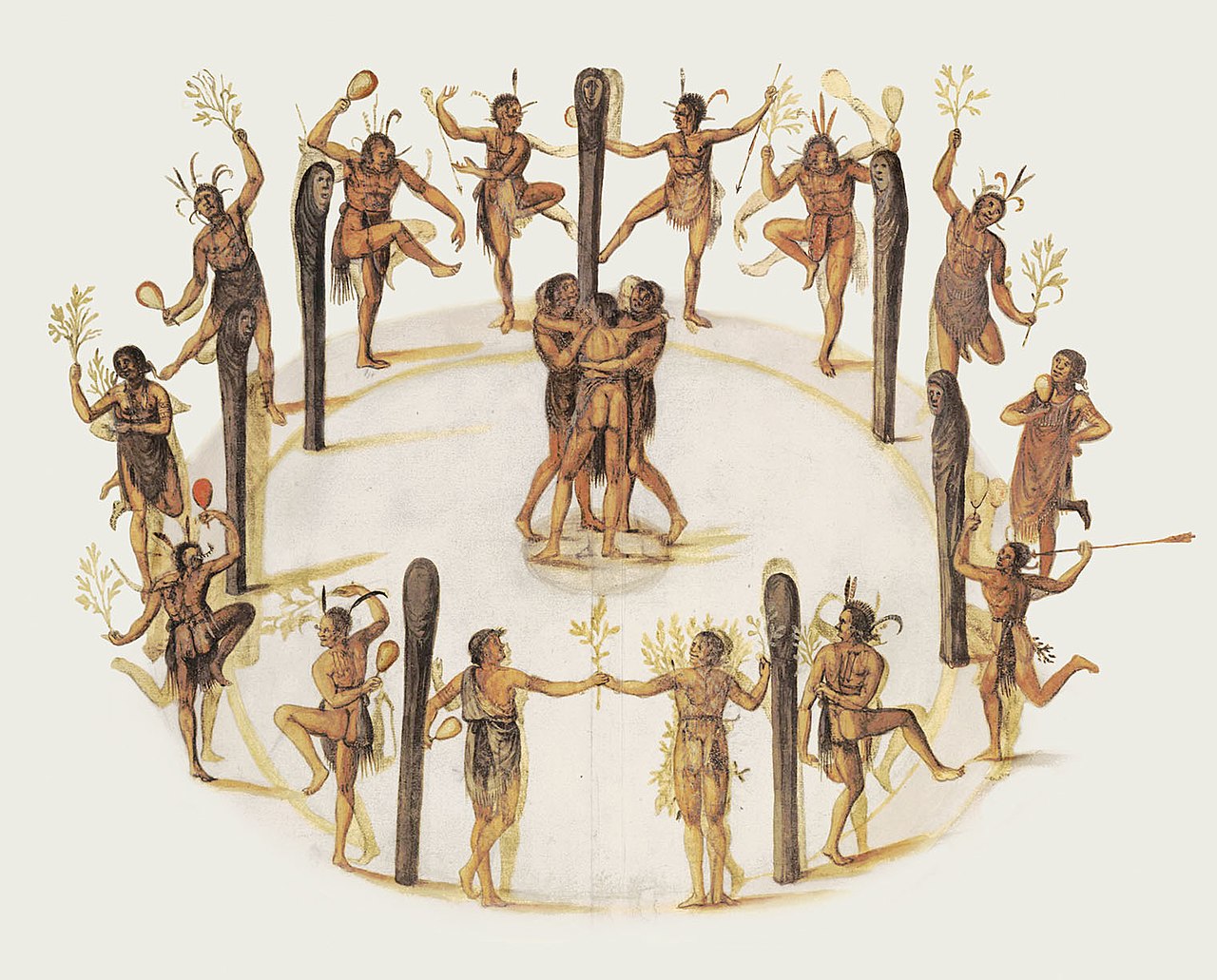

Secotan Indians’ dance in North Carolina.

Secotan Indians’ dance in North Carolina.Photo credits: Watercolor by John White, (British Museum, London) (Wikimedia Commons)

We brought home also two of the Savages being lustie men, whose names are Wanchese and Manteo.1

Communicating by gestures

In 1584, two ships sailed to America under captains Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe. This exploratory expedition sailed to Roanoke, off the coast of modern-day North Carolina, in an area named Virginia in honour of the Virgin Queen. Barlowe wrote an account of their journey which concentrated on the natural riches of a land of which “in all the world the like abundance is not to be found”.2His enthusiasm was probably informed by Raleigh’s ambitions; he told of local people who were welcoming, shared their food and were willing to trade.

Communication, however, was difficult: Barlowe reported an encounter on the third day of their sojourn with a man who betrayed no fear of the strangers on his soil. “After he had spoken of many things not understood by us, we brought him with his owne good liking, aboord the ships, and gave him a shirt, a hat & some other things, and made him taste our wine and our meat, which he liked very wel.3

That meeting was followed by one with Granganimeo, brother of King Wingina, who came to the shore near the English ships with a party of some forty or fifty “handsome and goodly people” and [B]eckoned us to come and sit by him, which we performed: and being set hee made all signes of joy and welcome, striking on his head and his breast and afterwards on ours to shew wee were all one, smiling and making shew the best he could of al love and familiaritie. After he made a long speech unto us, wee presented him with divers things which he received very joyfully and thankfully.4

Sign language clearly enabled some exchange of information as well as goods. It is easy enough to understand when Granganimeo demonstrated that a tin dish could be made into a breastplate to protect him from enemy arrows, or that his hosts on the ship were not to remove the “broad plate of golde, or copper” that he wore on his head 5 Observation could tell the explorers much about people’s clothing, boat-making, weapons, farming, fishing and cooking and allow comparisons with life in England to establish the distinction between members of the nobility and ordinary people.

Wanchese and Manteo

This approach did have its limits, however. Towards the end of his account, Barlowe reveals another source of information. He describes local geo-politics and warfare and acknowledges that his understanding of the conflicts and treaties in question comes from the two locals who had sailed back to England with them: Wanchese and Manteo. Wanchese was from Roanoke and Manteo was a werowance, or chief, from the island of Croatan. The settlers may well have been instructed to return with natives. Raleigh certainly made it the practice for his expeditions to Virginia and later, to Guiana and Trinidad, to enlist the help of local people. He probably knew that the Conquistadors had resorted to using captive-interpreters6 and he wanted middlemen who could serve England’s cause, having learned English and been introduced to Anglicanism.

When they reached England, these two men were not treated like exotica in the way previous indigenous visitors had been. They were presented at Court and then they moved into Durham House– a Crown property in London at Raleigh’s disposal– and began learning English. Their teacher was Thomas Hariot, the mathematician and astronomer who helped Raleigh with his navigational expertise and whose interests extended to languages. In addition to teaching the two visitors English, he learned their language, Algonquian, and devised a phonetic alphabet for it.7.This was to be of help on the second expedition to Roanoke, which set sail in April 1585 under the command of Sir Richard Grenville, with Wanchese and Manteo on board as well as Hariot and the illustrator John White.

Manteo and Wanchese could reportedly speak English by then. Wanchese did not wish to be involved with the Englishmen but Manteo acted as interpreter for Grenville and his successor, Ralph Lane. He helped with negotiations and participated in the choice of where to settle on Roanoke Island. On one occasion he saved a scouting party from extermination. He showed them that optimistic guesswork was not always the best way to understand a situation when he “… warned Lane that the sound of local people singing along the riverbank was not, as Lane thought, ‘in token of our welcome’ but rather ‘that they meant to fight with us’.”8 The volleys of arrows soon began.

Hostilities between settlers and the Algonquians made life impossible. All but a token group of 15 sailed back to England with Sir Francis Drake in 1586 – and Manteo went with them, along with two other Indians. He returned the following year with John White, now governor. Those left behind had disappeared, and Wanchese was implicated in their deaths. White sought revenge for the loss and Manteo was involved in the fighting. His role as intermediary on the English side appears to have been confirmed by his baptism in August 1587. He was also made Lord of Roanoke, a move that can be read as “an empty gesture and an impossible assignment” as the English had no power.9 This second Roanoke colony, the ‘lost colony’, also failed; White returned to England for supplies but was unable to deliver then until 1590 by which time the settlers– and Manteo – had vanished.

Wanchese’s and Manteo’s names endure today in the names of towns in North Carolina that can serve as reminders of the choices and constraints facing middlemen in fraught situations. The English settlement in Jamestown in 1607 gave rise to comparable tensions.

References:

- Barlow, A. The First Voyage to Roanoke, 1584. Documenting the American South, electronic edition, 2002, p. 12.

- Ibid, p. 2.

- Ibid, p. 3.

- Ibid, p.4.

- Ibid, p. 5

- Milton, G. Big Chief Elizabeth: How England’s adventurers gambled and won the New World. 2000, Kindle book retrieved from Amazon.com. Ch. 3.

- Ibid, location 915

- Vaughan, A.T. “Sir Walter Raleigh’s Indian Interpreters, 1584-1618″. In the William & Mary Quarterly, 3rd Series, Vol. LIX No 2, 2002, pp. 341-376, p. 351.

- Ibid, p 357.