The Umayyad Caliph of Cordoba, Abd ar-Rahman III (889/91 – 961) needed intermediaries as he sought to consolidate his rule, and they were almost always non-Moslems. There is some suggestion that by the mid-tenth century the Arab elites in al-Andalus had become closed in on themselves and reluctant to deal with non-Moslems1 Be that as it may, the Caliph’s protracted negotiations with the court of Otto I of Saxony involving both Hasday ibn Shaprut, a leader of the Cordoba Jewish community, and Recemund, a Christian court official, sheds some light on the complexities of language and politics at that time.

“At this time, Cordoba ambassadors are usually from ‘minority groups’, Jews or Christians, whose dual culture made into almost ‘natural’ intermediaries between the Umayyad Caliphate and Christian countries.”2

“There are many references in the Arabic sources to Christian members of embassies from Cordoba to Europe and Byzantium, but the Arabic historians supply little more than the names of these men, sometimes adding that they acted as interpreters.”3

Otto I’s embassy to Cordoba

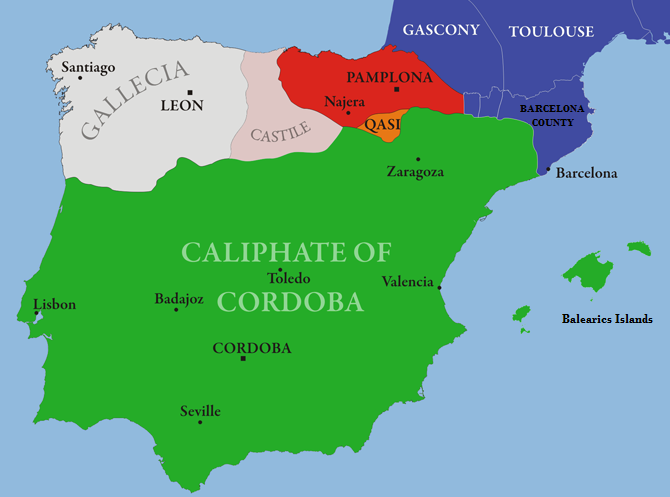

There were good reasons for Otto I – future king of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor – to send an embassy to Córdoba in the 950s. Aside from any broader diplomatic ambitions he might have entertained, he hoped that the Caliph might agree to use his influence with Muslim trouble-makers in Fraxinetum (modern La Garde Freinet). They controlled the mountain passes into Italy as well as long stretches of the coastline and were notorious for harassing travellers, burning monasteries, and impeding trade through acts of piracy.

The Benedictine monk John of Gorze agreed to act as an envoy for Otto I. He and two companions set out from his monastery near Metz to Cordoba in 953, bearing gifts and letters. They travelled through France to Lyon, sailed first down the Rhône and then on to Barcelona. Abd ar-Rahman III arranged for a safe-conduct for the party and had them housed in a palace near the Church of St Martin in Córdoba.

Diplomatic hitches

It was once they were settled that the complexities of the situation became apparent. The pirates of Fraxinetum might have seemed to be a straightforward issue but John of Gorze proved to be a prickly character. The account we have of his mission to Córdoba comes to us from a tenth-century copy of his life story which was written after his return home. It has to be read in the context of his faith and his commitment to the reform of his Benedictine order, which may explain why he did not seem prepared to “behave in accordance with the customs of the Muslim Court”4

One of the first people he met was Hasday Ibn Shaprut, the Caliph’s personal physician and trusted representative, who was a prominent figure at court and had often served as his intermediary. In addition to Hebrew he knew Arabic, Andalusi Romance (the dialect descended from Late Latin) and Latin, which we have to assume was the language he used in his unsuccessful attempt to prepare John of Gorze for his meeting with the Caliph. He had reason to fear that the letters carried by Otto I’s envoy would be deemed offensive to Islam and jeopardise the monk’s mission, but was unable to dissuade him from delivering them. The Bishop of Córdoba also failed to convince John of Gorze to present just Otto I’s gifts to the Caliph, not the letters.

An embassy to Frankfurt

It was decided to appeal directly to the Saxon court. Abd ar-Rahman III called upon Recemund, an Arabic-speaking Christian, to do the honours. He set off for Frankfurt in June 955. “His origin as a member of the indigenous community of al-Andalus affirms that he was a Latin speaker, and it was, presumably, in this language that he communicated with Otto.”5 Recemund was successful in that Otto I agreed to provide him with a letter couched in more moderate terms. He returned with the new missive in June of the following year. Some three years after John of Gorze’s arrival, his embassy was finally received by the Caliph.

A resolution of sorts

On the appointed day, “[s]oldiers lined the both sides of the road, carrying various kinds of weapons, whilst the cavalry displayed their horsemanship as the ambassadors walked from their residence to the city of Córdoba, and from the city to the Caliphal palace6

This display of might, along with conversations between John of Gorze and the Caliph about the nature of power, were the most productive aspects of this long-delayed meeting. Abd ar-Rahman III had no influence over the Fraxinetum community and was unable to help. John of Gorze left Córdoba with some three-years’ worth of experience of the Caliphate which may have been useful to Otto I as he consolidated and expanded his power. He defeated the Fraxinetum pirates in 973, perhaps prepared to take military action having learned that they were not loyal to the Caliph.

The bigger picture

The broader political context can be helpful here. Both Otto I and Abd ar-Rahman III aspired to political and spiritual authority over their subjects and sought outside support for their ambitions. Abd ar-Rahman’s enjoyed good relations with Christian Byzantium, which shared his hostility towards his rivals, the Fatimid Caliphates in the Maghreb. Constantinople was wary of Otto I’s rival imperial ambitions, which may have influenced the al-Andalus court’s response to John of Gorze’s embassy to Córdoba7

Abd ar-Rahman had welcomed a 949 delegation from Constantinople to strengthen his ties with Byzantium. The ritual exchange of gifts included a presentation to him of a copy of the work of Dioscorides On Medicine – on the medicinal properties of plants. No one could read it because it was in Greek. When the Caliphate appealed to Byzantium for help, Nicholas, a Greek monk was sent to oversee the translation of the text into Arabic. He was assisted by a Greek-speaker from Sicily, who is assumed to have also spoken Arabic as the island had been under Arab control since 830. Nicholas and is assistant later expounded the text of Dioscorides to a group of Andalusi scholars which included Hasday ibn Shaprut.8

Some scholars suggest that Nicholas taught the team Greek, others that the work was first put into Latin and then into Arabic. Whatever the solution, it was important to the Umayyad Caliphate to be seen as taking over from Baghdad in providing Arabic versions of early texts. The team work on Dioscorides set an example to the post-Caliphate era: the celebrated Toledo school might never have developed without the precedence set in interpreting and translation in Córdoba.9

References:

- Guichard, P.” Les Relations diplomatiques des Omeyyades de Cordoue” Oriente Moderno , 2008, Nuova serie, Anno 88, Nr. 2, p. 247.

- Ibid(My translation)

- Christys, A. Christians in al-Andalus, London and New York, Routledge, 2002, p. 108.

- Hitchcock, R. (2008). Mozarabs in Medieval and Early Modern Spain, Aldershot, Hampshire and Burlington, Vermont, Ashgate, 2008, p. 43.

- Ibid p.47.

- Abdurrahman A El-H. Andalusian Diplomatic Relations with Western Europe during the Umayyad Period (755-976) A Historical Survey, Beirut, Dar al-Irshad, 1970, p. 221.

- Fernández, F. “De Embajadas y Regalos entre Califas y Emperadores” AWRAQ No 7, 2013, p. 25.

- Fletcher, R. Moorish Spain, London, Phoenix, 1992, p. 69.

- Toral-Niehoff, I. Translations as Part of Power Semiotics: the Case of Caliphal Cordova,www.academia.edu/7399891/Translations_as_Part_of…, p.4